When it comes to energy codes and lighting, perhaps the most recognized of all is California’s Title 24 1 . In 1979 it became the first lighting energy code enforced statewide. Its principles have since heavily influenced all other energy codes in North America and much of the world. The next generation standards, Title 24-2022 are now under development.

Title 24 is admittedly not perfect, but to the professional designer it still allows good design. Title 24 development and change has always employed an open process where proposed changes are presented in public hearings and debated. Initially, the California Energy Commission (CEC) relied heavily on the IES’ Regional Energy Committee for ideas and input. As the design community grew and as lighting agents and manufacturers became savvier, designer influence increased. Today, thanks to lighting designers and the lighting industry, it is far better than it would have been had it been left to bureaucrats and energy wonks 2 . After all, the design community is concerned with quality and not just footcandles or watts.

WHAT’S GOOD ABOUT TITLE 24?

From the beginning, Title 24 has been written by persons who understood the challenges and differences among project types, and the need for glare control and other lighting quality provisions. Real projects are still used as models, and they include complex project types as well as simpler situations. Exemptions are allowed, such as not counting the lighting for a stage or allowing a decorative allowance for certain project types. In the hands of a good lighting designer, high quality projects complying with Title 24 have always been possible. Title 24’s philosophy and breakthroughs have also become part of both IECC and ASHRAE/IES 90.1.

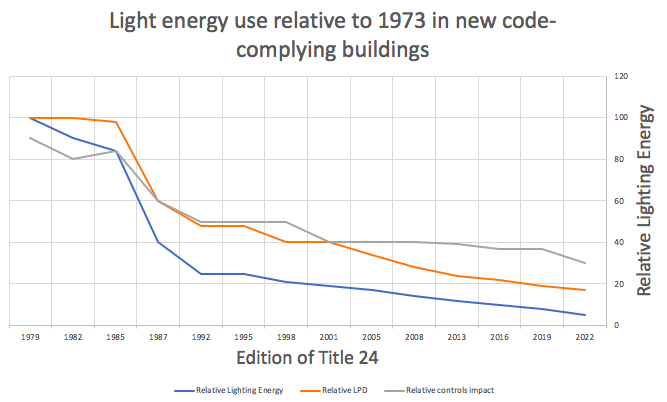

The impact of Title 24 has been exceptional. It has forced designers to learn to use cost effective and energy efficient technologies, and to provide sensible controls. Designers in turn demand new products and innovation, especially LED lighting and dimmable electronic controls. The results are shown in the attached diagram I call “Benya’s Curve” 3 , which shows that appropriate lighting can be designed today to operate at 90% less energy use than a comparable space in 1978. It is easy to brag about out industry’s achievement and hard to argue that lighting design has suffered.

WHAT’S BAD ABOUT IT?

From the beginning, lighting designers have looked upon California’s Title 24 energy code as limiting their creative options. That is at least partly true. Initially it served to limit incandescent lighting, but over time Title 24 played a series of ever-stronger hands to restrict every lighting technology. The worst was with compact fluorescent lighting, a generally awful light source forced into incandescent lighting situations with constantly poor results. Fortunately, LED lighting is so vastly superior that lighting designers can now achieve their goals without crummy color, flicker, poor dimming, or disastrous photometric performance. The 2019 standards are mostly rational and quality design is not a problem.

Perhaps the worst of Title 24’s current lighting requirements involves “JA8” – Joint Appendix 8, which imposes color quality, flicker limits, and other requirements on residential lighting. Originally intended to prevent LED technology from devolving as badly as compact fluorescent, JA8 requires every LED luminaire in a home to be certified by a certified lab and listed by the Energy Commission. That listing requires test reports for each SKU, which manufacturers say costs thousands of dollars each. For manufacturers who make a wide range of residential lighting products, the costs are prohibitive – and of course, need recertification if there is a change to a driver or LED module. Residential lighting designers also note that for major projects, the specified product may not be available two years after the specification and building permit – then what? Aren’t there enough options in LED lighting for a homeowner or designer to choose?

MAKING IT EVEN WORSE

About the year 2000, the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) began allowing utilities to claim energy efficiency savings from Title 24 changes they introduced – resulting in higher utility rates. Called “attribution,” this encouraged the utilities to take charge of Title 24 over the last two decades as they gathered to form and fund the Statewide Utility Codes and Standards Enhancement Team.

Today, the utility Team hires professional consultants to develop code change ideas and then to make formal proposals to the CEC known as Codes and Standard Enhancement (CASE) reports that have changed the character of Title 24 development. For example, a 2022 CASE report proposing outdoor lighting code changes consists of 236 pages of technical reporting, 112 tables, 46 figures, 14 appendices, references and a 5-page bibliography. These reports typically cost about $1,000 per page to produce 4 . For all practical purposes, this changes the public process on which Title 24 was founded and has turned ongoing code development into an expensive and bureaucratic process in which voluminous and costly CASE reports have become the voice of change. How can an individual designer afford to participate or to affect the outcome?

Worse yet, because of current success at reducing lighting energy the CASE proposals are increasingly having to nit-pick Title 24 to find rational opportunities. Having already reduced outdoor lighting power allowances by nearly 50% in the last decade, the above-mentioned CASE proposal now wants to alter light levels by making lighting zone interpretations and descriptions different from Table 26.4 of the IES 10th Edition Handbook. The net effect could lower Title 24’s lighting power allowances such that recommended lighting levels from Handbook Chapter 26 may not be able to be achieved. I believe first in the professional responsibility of the designer to assess the design situation and correctly light it, and a code that prevents this is a bad one.

Historically, the California Energy Commission expected code changes to be consistent with IES recommendations and good design practice. Realizing the overbearing advantage in resources that the utility team has, the IALD and IES Sections in California began to organize this year to step in with and on behalf of the lighting community to counterbalance the weight of CASE reports and the controlling efforts of the utility team. As an industry we have been remiss in not identifying this particular trend and fighting it. But we must. In my 2020 LightFair program with Clifton Lemon, our topic is “Own the Code” because we should. •

1 Title 24 of the California Code of Regulations is the state’s building codes including the building code, plumbing code, HVAC code, electrical code, sustainability code and other sections. Part 6 is the Building Energy Efficiency Standards. Among lighting professionals, the phrase “Title 24” needs little explanation.

2 A person who takes an excessive interest in minor details of political policy.

3 LD&A, May, 2018, “Our Work is Done Here”, by James Benya.

4 I have first-hand experience with developingCASE reports.

This article originally appeared in the August 2020 issue of designing lighting.