Implementing A Five-Step Human-Centric Lighting Design Process for Your Next Project

At the IALD Enlighten Americas conference, Dr. Kevin W. Houser, IALD, and Dr. Tony Esposito, Ph.D., explored the intricacies of human-centric lighting (HCL). They addressed the challenges, misconceptions, and evolving understanding of HCL’s effects on human well-being. Both emphasized the need to question current assumptions and apply scientific insights to lighting design.

Defining Human-Centric Lighting: Integrative or Misleading?

Kevin Houser noted that modern humans spend most of their time indoors. The spaces we design affect not only our visual performance but also our physiological and psychological responses. He referenced the International Commission on Illumination’s (CIE) definition of “integrative lighting,” Houser feels better reflects the balance between visual and non-visual effects on human physiology.

While “human-centric lighting” sounds appealing, Houser pointed out that it often gets reduced to a marketing phrase. He compared it to Nike’s slogan “Just do it,” which carries motivational and commercial weight. Houser cautioned that health claims attached to lighting products might signal over-commercialization. “If you see a health claim on a lighting product, it’s a strong indication it’s not natural light,” he remarked, underscoring the value of natural daylight.

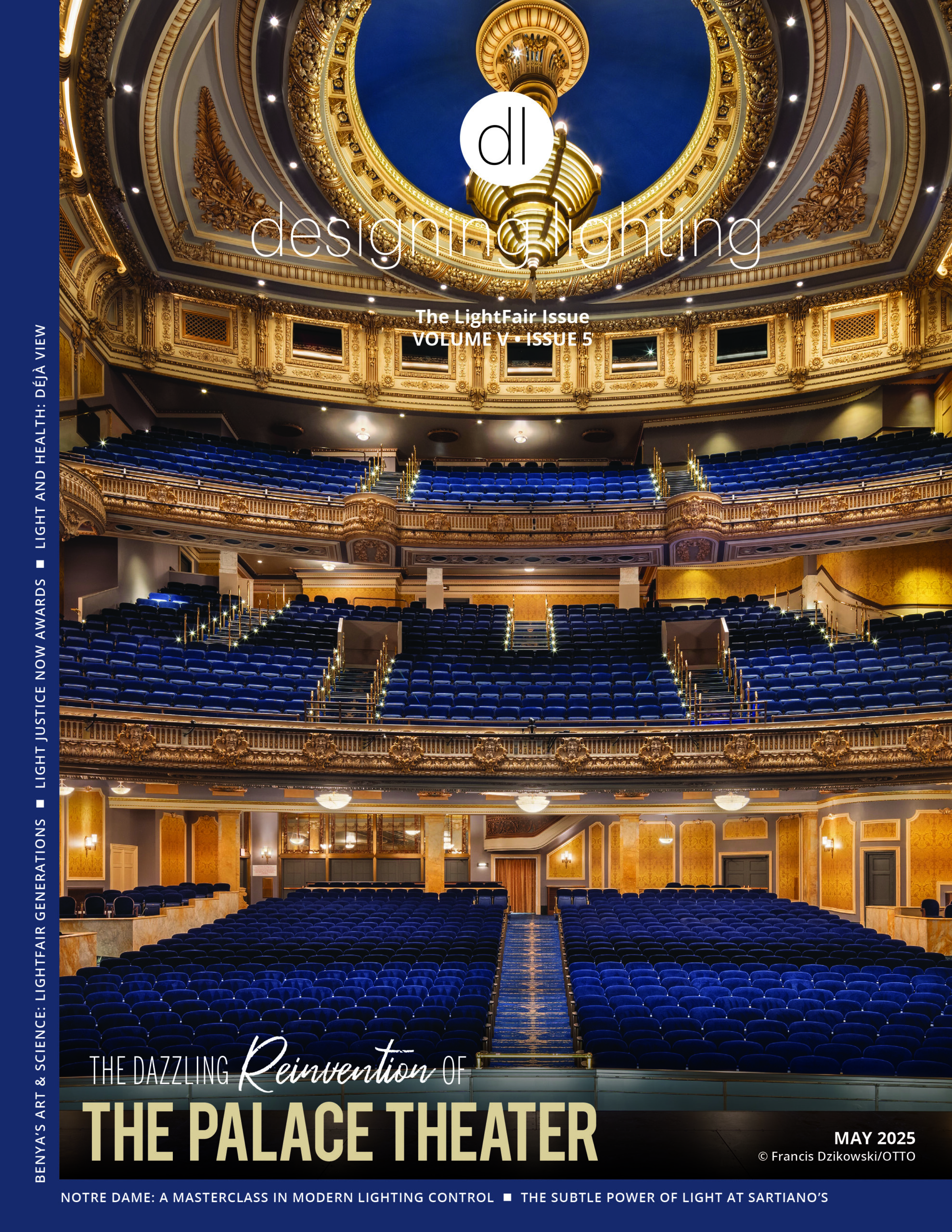

Kevin Houser discusses human-centric lighting design at the IALD Enlighten Americas Conference

Addressing the Marketing vs. Reality Gap

Houser explained that human-centric lighting should mimic natural light cycles, balancing bright, dynamic daytime light with restful darkness at night. However, many indoor spaces disrupt this natural rhythm, leading to health problems, including circadian misalignment.

He displayed market predictions showing that the HCL market, valued at $1 billion in 2020, could exceed $5.5 billion by 2027. Yet, Houser expressed skepticism, suggesting that some products labeled as HCL might not support human health as claimed. “Human-centric lighting is not a plug-and-play solution,” Houser explained. It requires thoughtful, holistic design considering human physiology and environmental impacts.

The Dangers of Misguided HCL Solutions

Houser also raised concerns about anthropogenic light at night (ALAN), which harms both humans and ecosystems. He stressed that light pollution disrupts circadian rhythms, delays sleep and poses risks to wildlife. Many species, including birds and insects, depend on natural light cycles for survival. Houser urged the industry to think critically about the broader environmental consequences of lighting decisions.

His presentation highlighted the negative effects of artificial light at night, both direct and indirect. While the goal is to make lighting human-centric, it’s essential to consider how light impacts the entire ecosystem.

Measuring Biological Potential

One of the major challenges in HCL is determining how to measure the biological potential of light. Two main methods exist: one based on the spectral response of photopigments in our eyes, and the other focused on how light affects melatonin suppression. The CS and Melanopic EDI models were discussed, with no favoritism toward either model. designing lighting (dl) magazine published an article in December 2022 explaining both models.

Houser emphasized that timing is critical for circadian health. “Even if the spectrum and intensity are right, bad outcomes can occur if the light is presented at the wrong time of day,” he said. His presentation featured a logistic curve to show how light intensity and spectrum affect melatonin suppression and alertness.

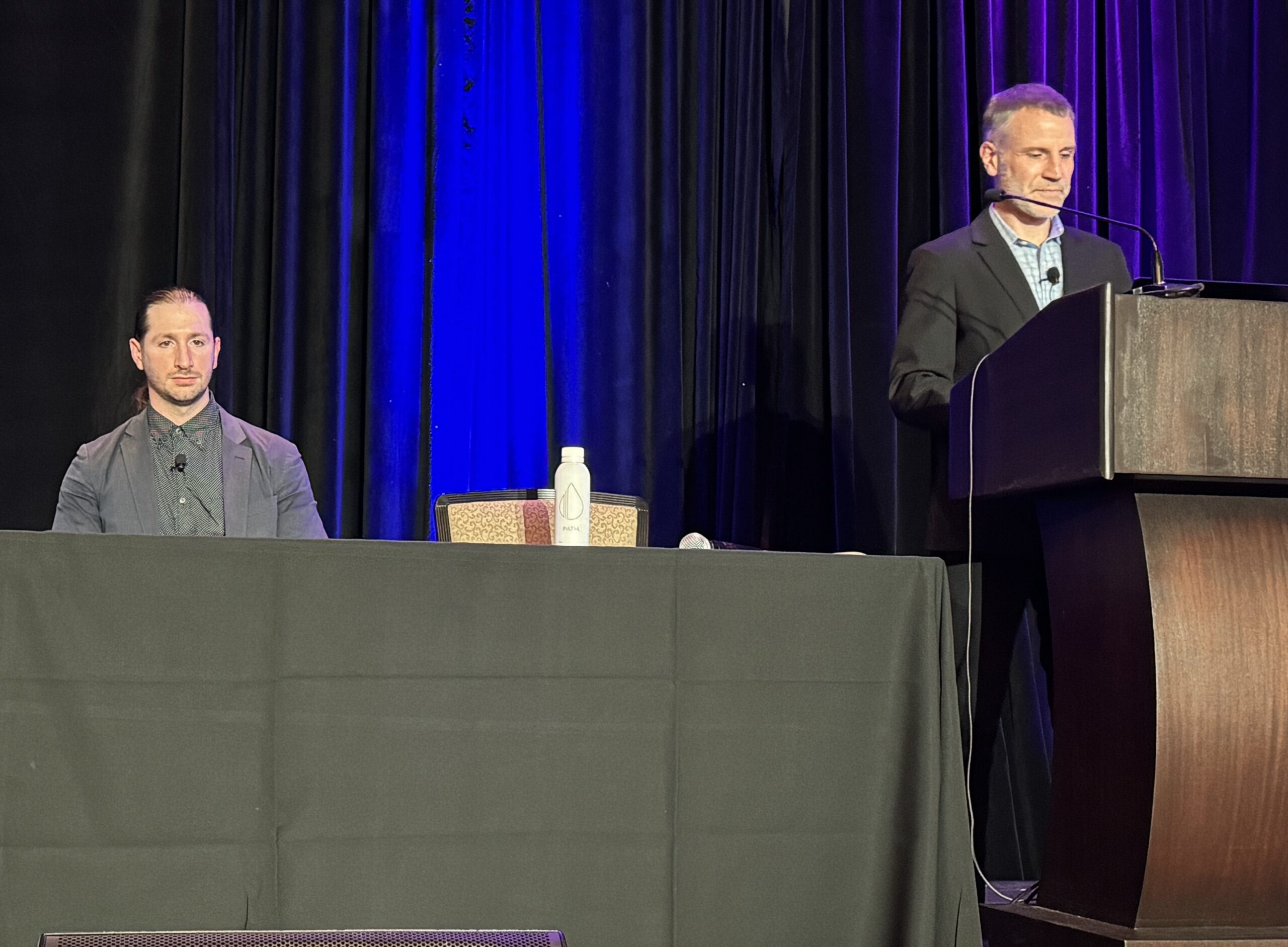

Dr. Tony Esposito discusses the five-step human-centric lighting design process at the IALD Enlighten Americas Conference

Tony Esposito’s Five-Step Design Process

Tony Esposito followed with a practical framework: a five-step design process for human-centric lighting. His approach helps lighting professionals make defensible design decisions. The steps include:

- Characterize the lighting application.

- Understand the sleep-wake cycles of occupants.

- Identify sleep needs.

- Apply human-centric lighting guidance.

- Build specifications.

In healthcare environments, Esposito explained, the design must balance the needs of both day-active caregivers and night-active workers while also considering patients’ circadian health. Each project requires a tailored approach with no one-size-fits-all solution.

Esposito also critiqued the use of correlated color temperature (CCT) as a predictor of circadian stimulus. He described CCT as a misleading metric, instead advocating for more nuanced spectral engineering. His humorous suggestion to rename “intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells” as “spiders” illustrated how clearer communication is needed between designers and scientists.

Conclusion: Myth, Magic, or Metaphor?

Houser wrapped up the session by reflecting on whether human-centric lighting is a myth, magic, or metaphor. It’s not a myth, as the biological and physiological effects of light are well-established. Nor is it magic—effective design strategies can achieve human-centric lighting. Instead, Houser views it as a metaphor—a reboot of “lighting quality” that encompasses both visual comfort and biological impacts.

The takeaway was clear: human-centric lighting holds promise but requires thoughtful, scientifically grounded design. As the HCL market grows, lighting professionals must focus on creating sustainable, scientifically sound lighting solutions rather than falling for marketing hype.

Personal Anecdote: A Dinner Conversation to Remember

On a personal note, I had a few burning questions and later that evening, I managed to corner Tony at an off-site dinner sponsored by Acuity. We were deep in conversation, with an empty seat between us, when a gentleman approached, plate in hand, and politely asked if he could join. Without hesitation, I said, “Of course!” He sat down, and Tony, with perfect comedic timing, added, “As long as you’re ready for a riveting discussion about intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells.” The gentleman blinked, paused for a moment, and then, without a word, quietly got up and moved to another table.

Read about Achieving Transparency in the Lighting Industry, here.